Every year, on the second Sunday in February, American capitalism gathers around a single, electronic campfire to watch the one of the last remaining monocultural events in human history.

We tell ourselves we are tuning in for football, but many of us will happily confess we are strictly there for the commercials.

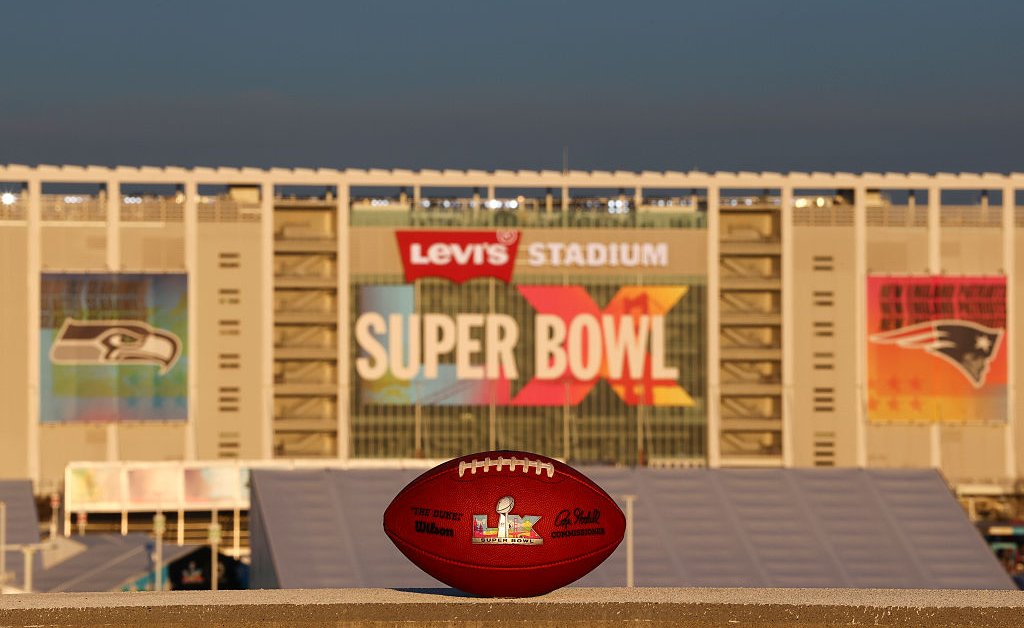

This Sunday, for Super Bowl LX, brands have paid a record-breaking $8 million for 30 seconds of airtime, roughly $266,000 per second, to interrupt the game. A handful of prime spots are going for up to $10 million for 30 seconds.

To understand how we arrived at a moment where a Pringles spot starring Sabrina Carpenter costs more than the GDP of a small island nation, we have to look backward. Advertising is not just a business; it is the fossil record of human desire. And the first fossil we have was found not on Madison Avenue, but in Thebes, Egypt.

The first recorded advertisement, dated to roughly 3,000 B.C., is believed to be a piece of papyrus written by a fabric merchant named Hapu. According to archaeologists, the notice was about a man named Shem who had escaped slavery. But Hapu pivoted midway through the text. After offering a reward for Shem’s return, he seamlessly transitioned into a pitch along the lines of: “The shop of Hapu the Weaver, where the best cloth is woven to your desires.” It was likely the world’s first, albeit evil, bait-and-switch.

In the ancient world, advertising was limited by a simple bottleneck: literacy. In Egypt, Greece, and Rome, messages were painted on walls (the frescoes of Pompeii are littered with political campaign ads and ads for gladiatorial contests) or shouted into the air. In the Middle Ages and Elizabethan England, the town crier was the primary broadcast medium. These men were paid to bellow news of royal decrees, but they moonlighted as walking billboards, paid by local merchants to shout about the arrival of fresh fish or wine.

Because most customers couldn’t read, early advertising was visual. This is the era of the signboard—the Cobbler’s boot, the Baker’s sheaf of wheat—symbols that hung over muddy European streets to tell the illiterate masses where to spend their coin.

Mass-market advertising as we know it was born from the Industrial Revolution. It solved a new problem: surplus. Before steam power, you made goods for your neighbors. After steam power, you made more soap than your village could wash with in a lifetime. You needed strangers to buy your product.

The first paid newspaper advertisement in the U.S. appeared in 1704 (a real estate solicitation in the Boston News-Letter), but the industry exploded in the 20th century.

This led to two distinct Golden Ages of advertising. The first was the peak of print. For decades, the Sunday newspaper and the glossy magazine were the titans of ad revenue. This dominance arguably peaked around 2000, just before the internet began its slow demolition of print media’s business model. According to Pew Research Center, newspaper ad revenue fell from roughly $49 billion in 2006 to under $10 billion by 2022.

The second Golden Age was the reign of television. From the Mad Man era of the 1960s through the sitcom dominance of the 1990s, TV was the only way to reach tens of millions of people at once.

While global TV revenue is still growing, in the U.S., the medium is arguably in decline. Linear TV ad spending is projected to continue its steep drop to roughly $55 billion in 2026, a shadow of its former hegemony as eyeballs migrate to TikTok and Netflix, according to MediaPost.

The internet didn’t just add a new medium; it inverted the business model. Google and Facebook (Meta) replaced “broadcasting” (shouting at everyone) with “narrowcasting” (whispering to the one person who wants to buy).

This shift has created a market of staggering proportions. In 2026, total U.S. advertising spending is projected to approach $500 billion, fueled by spending on ads for the Olympics, the World Cup, and the midterm elections. Digital advertising is expected to account for the vast majority. Meta generated over $196 billion in advertising revenue in 2025 alone. Alphabet remains the heavyweight champion of the digital advertising world, converting search intent into hundreds of billions in revenue. Amazon is now eating into the duopoly’s share by selling ads on Prime Video and across its retail empire.

This brings us back to Super Bowl LX. In an era where Google allows advertisers to target hyper-specific groups of consumers for pennies on the click, why pay $8 million for a 30-second spot?

Because the Super Bowl is the only thing Google cannot replicate. It is the last bastion of true human-to-human connection. In a fragmented world, it is one of the only times 120 million people look at the same screen simultaneously. The Super Bowl ad is no longer just a commercial; it is a vanity metric, a flex, and a signal of cultural relevance. And it is the only place where a brand can guarantee that its ad will be watched by a group of people at the same time, in one place, together.

This year, the price for that cultural relevance has hit an all-time high of $8 million. And the lineup reflects the desperation to capture attention in a distracted world. We are expecting Ben Affleck to return for Dunkin’, Kendall Jenner to promote online betting company Fanatics Sportsbook, and Bud Light to deploy the Avengers of American populism: Peyton Manning and Post Malone.

Our fascination with Super Bowl ads exposes a deeper truth about contemporary capitalism. Attention has become so extracted, personalized, and monetized that the rare moment when it is collectively volunteered now commands a fortune. The Super Bowl is not an escape from the attention economy, but its apex, a night when advertising sheds its stealth and announces itself as spectacle. The billions spent are not for creativity or charm, but for the last remaining illusion of shared experience—proof that in our fractured culture, even togetherness has its price.

We may have traded the town crier for the celebrity cameo, and the papyrus for the pixel, but the transaction remains unchanged. We pay with our attention, they pay with a spectacle, and for one Sunday a year, we all agree the price is right.

Uncategorized,EconomyEconomy#Super #Bowl #Commercials #Teach #Capitalism1770550417