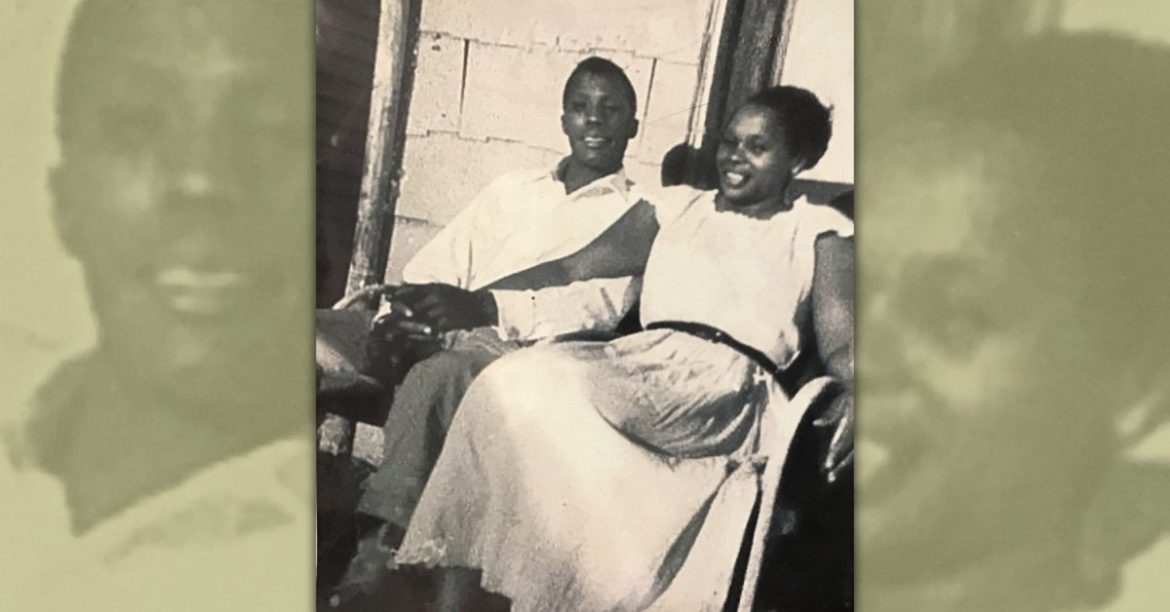

In my house in Providence, there’s an old photograph of my parents hanging on the living room wall that I look at every day. They had been married for 11 years when it was taken. In the picture, they’re sitting next to each other in the backyard on a late summer’s afternoon. They are smiling and holding hands. To all the world, they look like they have arrived—like they have everything they’ve ever wanted.

But it’s 1957, and in America, Black people still have to worry about the possibility of getting lynched. Jim Crow in the south and racism everywhere else was rampant. Let me remind you that 1957 was only two years after the Montgomery bus boycott and the murder of Emmitt Till.

The year this photo was taken, a recently passed civil rights bill was proving difficult to enforce. That year, Richard and Mildred Loving would begin a nearly 10-year odyssey of banishment from their home state of Virginia, that was finally ended by a Supreme Court ruling that legalized interracial marriage. 1957 is the year president Eisenhower reluctantly federalized the National Guard in Little Rock, Ark. to escort nine Black children through a hostile white mob to attend Central High School.

I look at that photo and think of those times. My parents had every reason to worry about their own safety and their children’s, too. It must’ve been something like living under a state of siege. But that was their life.

And yet there they are, holding hands and smiling. Their contentment and their connection is undeniable. Given what I knew about their circumstances, I looked at that picture and for the longest time was at a total loss to explain how they could have been so happy. Bear with me.

My parents, Mamie Lee Gohagon and George Washington Green, were childhood friends born and raised in Selma, Ala., in the mid-1920s. In coming to terms with the hellish maelstrom of World War II and the ongoing plague of American racism, these two friends would go their separate ways.

Mom left home for what she hoped were greener pastures in Louisville, Ky. Dad left Selma twice: The first time was to the Atlantic because of his enlistment in the Navy. The second time was in order to save his own life from a lynch mob.

But when the war ended, not only would they find themselves unexpectedly reunited, but just as surprising, their friendship was now blossoming into love.

They have very distinct personalities, to be sure, and weren’t always in agreement, but having both grown up in the “belly of the beast,” their lives ran parallel in many respects.

Both had spent their entire lives chafing under the terror of bigotry, and from the hypocrisy being exposed by a heinous, toxic legacy of institutionalized double standards. So as a consequence, I believe that as kids, they acquired a precocious awareness of just how fragile, tenuous, and ephemeral everything is, and of how vulnerable we all are.

A hard won resilience would remain a constant that not only allowed them to embrace the long view, but to also to maintain the capacity to accept life’s challenges without ever losing hope. My parents had left Selma separately and under quite different circumstances, but doing so was proof of the higher expectations they had for themselves.

I look at that photo now and recall how years later, Mom would advise that I always pay attention, remain focused, apply myself, have some gratitude and some appreciation—but never get ahead of myself and never get too carried away because, as she was fond of saying, whatever your circumstances, no matter who you are, remember that “Now is not forever.”

Mom was a very proud, very confident woman at a time when it was especially dangerous for her to be that way. She was highly intuitive and possessed a wonderfully nuanced memory reminiscent of an African griot. She was bright, resourceful, and determined—very hands-on and unapologetic about being her hard-working, passionately authentic self.

Dad, on the other hand, was soft-spoken, gentle, empathetic, and accountable. He was uncommonly patient with a fierce self-discipline, driven by a big-picture awareness that kept him from hardly ever speaking or acting impulsively. He was unpretentious, optimistic, good with numbers, and possessed a life-long reverence for the soil and for life in general.

I believe they found in each other someone they could trust implicitly; someone who not only loved them, but who also understood, protected, and accepted them on a seemingly molecular level. What Dad had found in Mom was his perfect compliment. And Mom had found in Dad a man so secure in who he was that she’d never have to worry about him trying to remake her. Mom had indeed found her champion.

Because of racism and sexism, my parents shared the status of outcast, so being unjustly written off and facing disproportionately long odds was nothing new. But what had changed was that now they were no longer bearing this burden alone. There could be no better time for looking at each other, taking stock, and gathering themselves. The deliverance they were seeking had to start from within.

Together, they set a course towards a balanced, equitable world of their own design: a 180-degree turn from the world they inherited.

In a simple ceremony conducted by a justice of the peace, they were married on March 16, 1946 in Jeffersonville, Ind. Afterwards, the 22-year-old bride and her 21-year-old groom would scoot back across the Ohio River to begin their new lives together in Louisville, Ky.

Their past had now been breached. They had left Selma, and the war was over. But the change in scenery was just that, because there was no end to and no escape from racism.

But the leap of faith, a life-affirming ritual of marriage, cemented their commitment to one another, and became the cornerstone of their unshakeable faith in a better future for themselves, and for any children they may have.

They would eventually have nine children, of which I am the fifth. But they would never have a lot of money in the bank. They would never own a car, and because of Jim Crow, they had only been granted a third-grade education. But beyond any doubt, they remain the wisest, the finest, and the most generous people I have ever known.

They were “to have and to hold” for 59 years until Mom passed away in 2005. She was 81. Dad told me that letting her go was the hardest thing he’d ever had to do. He then said, “I’m fine, but I’ll never be the same.” He told me that every day he lived was still a blessing. He passed away in 2015 at the age of 90.

My parents never failed to regard themselves as blessed, especially in the darkest of times. They would never lose their sense of humor. They would never relinquish their humanity, or fail to acknowledge that same divine spark in others.

I look at that photograph now, and I no longer feel as perplexed about just how and why they were able to attain and maintain such equanimity; which is not to say that I don’t still regard that level of grace as something miraculous.

But that being said, grace is a miracle that’s always within our reach.

The year the photograph was taken, 1957, was also the year the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. established the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. It was that year Sputnik was launched. It also happened to be the year my twin sister and I entered the first grade.

I look at that photograph these days and now I, too, am smiling.

Regardless of age, we are all somebody’s child. Having children is the closest we will ever come to being immortal. My grandparents were sharecroppers, and they must have known people who had been slaves. My siblings are lawyers, a chef, a social worker, a musician, a veteran, a nurse practitioner, and a college professor and author.

Read more: What It Means to Bury My Ancestors Twice

We are the evidence that our parents lived, and as part of that legacy, hopefully, we’re also the proof that though our parents may be gone, they are still having a positive influence in this world.

Yes, even in the darkest of times, hope persists. Love persists, and life goes on.

We need not ever act like compassion, fairness, and decency are scarce natural resources only to be hoarded or selectively doled out in piecemeal fashion. Believe me when I tell you, there’s always been enough to go around.

So while we are still here, while we can still make a choice, while we can still make a difference, let our intention always be to develop the courage to act in good faith, to acquire the wisdom that sees the bigger picture, and to find resilience to weather the storm.

May we live with a sense of purpose as well as one of urgency because, as my mother told me, now is not forever.

Uncategorized,RaceRace#Love #Parents #Answer #Jim #Crow1769947276