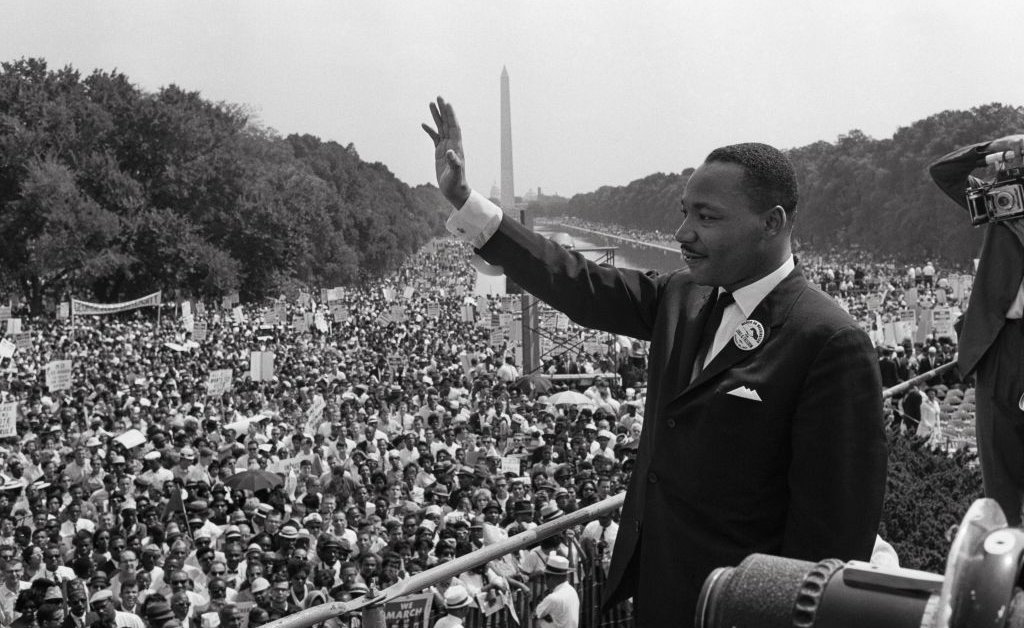

Each year on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, we return to Dr. King’s vision of the “beloved community”—a society grounded not only in the absence of injustice, but in the presence of dignity, shared responsibility, and genuine belonging. Too often, however, we remember that vision as moral rhetoric rather than a concrete mandate, something to admire rather than something to build.

For much of the last century, racial justice in America has been understood primarily as a defensive project. We identify discrimination, name a violation, and seek a remedy, often in court. This work has been indispensable. It dismantled Jim Crow, opened schools and workplaces, and affirmed the basic principle that discrimination has no place in a democracy.

But today, that framework is no longer sufficient on its own. Not because discrimination has disappeared—it has not—but because racial inequality increasingly operates through systems that rarely announce themselves as discriminatory. Inequality is produced by zoning rules that restrict affordable housing, by transportation systems that isolate neighborhoods, by public investments that consistently bypass certain communities, and by market dynamics that displace long-standing residents. These systems are often described as neutral, efficient, or inevitable. Yet their effects are deeply racialized.

The result is a troubling paradox. We live in a country with courts and laws formally committed to equality. But in practice, we too often tolerate patterns of racial inequality that are durable, predictable, and profound. This disconnect reveals a deeper problem, not only with civil rights enforcement, but with how we think about justice itself.

Justice is not only the absence of discrimination. It is the presence of conditions that allow people and communities to live with dignity, stability, and opportunity. And those conditions do not arise naturally. They are shaped intentionally by law, policy, and public investment.

Consider displacement. Across the country, Black communities are being pushed out of neighborhoods they have called home for generations. This is rarely framed as a civil rights issue. It is explained instead as the result of market forces or urban “revitalization.” But displacement is not an accident. It is the foreseeable outcome of decisions about housing policy, land use, transit, and development—decisions that determine whose presence is protected and whose is treated as expendable.

Or consider infrastructure. Highways that cut through Black neighborhoods, transit systems that connect wealthier areas while bypassing others, environmental hazards concentrated where political power is weakest. These are not relics of the distant past. They are ongoing examples of how physical systems distribute advantage and vulnerability. Infrastructure shapes who can get to work, access health care, survive climate disasters, and participate in civic life. When infrastructure fails communities, it fails democracy.

Traditional civil rights tools struggle to address these harms not because they are misguided, but because they were designed for a different problem. Much of our legal framework is oriented toward identifying intentional discrimination by a specific actor. But today’s inequality is often structural, cumulative, and diffuse. It has no single villain. It unfolds over time. And it is embedded in systems that appear race-neutral on their face.

This does not mean we should abandon civil rights law. Strong enforcement remains essential. But enforcement alone cannot do the full work that justice requires. What we need is a complementary approach that treats racial justice not only as something we defend against violation, but as something we must actively build.

Dr. King understood this distinction well. To him, the beloved community was never simply about restraining harm or condemning injustice after the fact. It was about constructing the social, economic, and political conditions that make equality durable—conditions that allow people not merely to coexist, but to live together with mutual concern and shared fate. The work of justice, as King envisioned it, was fundamentally constructive.

Building justice means asking different questions. Not just: Was there discrimination? But: What systems are producing these outcomes? Who benefits from their design? Who bears the costs? And what would it take to redesign them so that communities can flourish rather than fracture?

It also requires expanding our understanding of harm. Inequality is often experienced collectively. When a neighborhood loses affordable housing, a community loses stability. When public investment bypasses certain areas, residents lose access to opportunity. When displacement erodes social networks, people lose the support systems that make daily life possible. These are community-level injuries, and they demand community-centered solutions.

This approach is not a departure from our history. It is a continuation of it. In each of the nation’s great moments of progress, justice advanced not from restraint alone, but from design—reconstruction paired the end of slavery with schools; voting protections paired with federal enforcement. The New Deal combined regulation with social insurance and public investment. The civil rights movement demanded not only the end of segregation, but access to jobs, housing, and political power. In each case, equality became more durable because it was built into the structures of daily life.

Today, as courts narrow the meaning of equality and policymakers retreat from race-conscious remedies, we face a choice. In recent decisions, the Supreme Court has rejected race-conscious admissions in the name of formal neutrality, raised the bar for proving racially discriminatory gerrymandering, and narrowed the ability of voters to challenge practices that deny meaningful access to the ballot. Together, these rulings reflect a constricted vision of rights—one that treats inequality as legally irrelevant so long as it is produced by ostensibly neutral rules. We can continue to rely exclusively on tools designed to stop yesterday’s harms. Or we can pair those tools with a more ambitious project: building justice into the systems that shape where people live, how communities function, and who gets to belong.

Justice is not only a shield we raise when harm occurs. It is a blueprint for the beloved community we are trying to create. On this Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the question is not whether we honor Dr. King’s words. It is whether we are ready to build the beloved community he envisioned—one in which dignity, belonging, and opportunity are not aspirational ideals, but lived realities.

Uncategorized,politicspolitics#MLK #Taught #Justice #Requires #Building #Community1768825295